NA

E

K

VOLUME 1, NUMBER 1 / F A L L 2 0 0 8

JOURNAL OF

JOURNAL OF

SCHOOL CONNECTIONS

EDITORS

Jennifer J.-L. Chen, Kean University Diane H. Tracey, Kean University

EDITORIAL REVIEW BOARD

Janice Almasi

University of Kentucky

Raymond Bandlow

Fort Lee Public Schools, New Jersey

Frank J. Esposito

Kean University

Ted Kolderie

Education|Evolving

Diane Lapp

San Diego State University

Kathleen F. Malu

William Paterson University

Monica Miller Marsh

Desales University

Lesley Mandel Morrow

Rutgers University

Susan Polirstok

Dean, College of Education

Kean University

Flora Rodriguez-Brown

University of Illinois at Chicago

Michael Searson

Kean University

Cynthia Shannahan

University of Illinois at Chicago

Tony Xing Tan

University of South Florida

Sharon Walpole

University of Delaware

Xiao-lei Wang

Pace University

Louise C. Wilkinson

Syracuse University

John W. Young

Educational Testing Service

GUEST REVIEWERS

Xiaodong Liu

Brandeis University

Martin Gliserman

Rutgers University

CALL FOR REVIEWERS

The JSC is seeking manuscript reviewers with expertise in a variety of areas in

education. Reviewers’ contribution will help ensure that the articles published are

of the highest quality. To facilitate the process, an electronic copy of guidelines and a

recommendation form will be attached with each manuscript sent for review. Written

feedback from reviewers is expected to be communicated electronically within a month

of a manuscript’s receipt. Acknowledgement of reviewers’ contribution will appea

r

in each issue during tenure of service, and a letter of recognition will be provided at the

conclusion of each academic year. Please see the enclosed information about

JSC. We

invite you to join our Editorial Review Board. If you are interested, please email your

CV indicating your areas of expertise to [email protected]. Thank you for your consideration.

JOURNAL OF

S

CHOOL CONNECTIONS

The mission of JSC is to disseminate original, empirical research and

theoretical perspectives devoted to enhancing student learning and teaching

practices from preschool through high school. It is committed to bridging

theory and practice, and making research findings accessible to teachers,

researchers, administrators, and teacher educators.

JSC is an interdisciplinary, peer-reviewed publication founded by the College

of Education at Kean University. Published biannually (Fall and Spring),

JSC disseminates empirical quantitative and qualitative studies that explicitly

present a clear introduction, literature review, research design (research

question(s) and methodology), results/findings, discussion, limitations, and

educational implications.

The submission process. Please email an electronic copy of your manuscript

(with all identifying information removed) and a cover letter to [email protected].

The cover letter should state the authors’ names, institutional affiliations, and

contact information (email address, phone number, and address). It should

also contain a statement explicitly certifying that this manuscript has not been

previously published or under concurrent consideration elsewhere. Each

manuscript must be accompanied by an abstract of 100-150 words.

The review process. Manuscripts submitted to JSC for consideration are

first reviewed internally by the editors. Those that meet the initial review

criteria and fulfill the mission of

JSC will be sent out for external peer review.

The criteria for evaluating the manuscripts include: 1) significance of research

and/or theoretical contribution; 2) soundness of the research methodology; 3)

clarity of the writing in English; and 4) adherence to the style guidelines set

forth in the Publication Manual of the American Psychological

Association

(5th ed., 2001). Only manuscripts that meet these criteria will then be blind

reviewed by at least two peers, a process that usually takes 1 to 3 months.

Length of manuscript. A manuscript should be 25-35 pages (including

references, tables, and figures). All manuscripts must be page

numbered and

double-spaced in 12- point font with 1-inch margins all around.

All inquiries should be sent to:

Jennifer J.-L. Chen & Diane H. Tracey, Editors

Journal of School Connections

Dean’s Office, College of Education

Kean University

1000 Morris Avenue

Union, NJ 07083

E-mail: [email protected]

©2008 by Kean University.

JENNIFER J.-L. CHEN

and

DIANE H. TRACEY

Editors’ Introduction 1

SHUI-FONG LAM

and

WING-SHUEN LAU

Teachers’ Acceptance of Peer

Coaching: Impact of Collegiality and

Goal Orientation

3

MARGARET

FREEDSON

Supports for Dual Language

Vocabulary Development in

Bilingual and English Immersion

Pre-kindergarten Classrooms

25

SUZANNE

VISCOVICH,

ROBERT

ESCHENAUER,

RICHARD SINATRA,

and

T. MARK BEASLEY

Connecting Critical Thinking,

Organizational Structures and

Report Writing

63

RACHEL BROWN

Teachers’ Attempts to Teach

Comprehension Strategies Explicitly

During Core Instruction

87

CONTENTS

©2008 by Kean University.

JOURNAL OF

S

CHOOL CONNECTIONS

Volume 1 Number 1 Fall 2008

Editors’ Introduction

Welcome to the inaugural issue of the Journal of School Connections (JSC)!

Launching any scholarly journal is a tremendous undertaking that requires

rigor, commitment, persistence, and time. However, without the necessary

support and collaboration,

JSC would not have been debuted. We are

particularly grateful to President Dawood Farahi of Kean University for his

support, and to Dr. Frank Esposito (former interim dean of the College of

Education) for initiating the idea of establishing a refereed journal that would

advance from a well-established but college-based journal known as

School

Connections (founded by Dr. Dorothy Hennings, a Kean professor emerita).

Hence, it is only fitting that we named this new scholarly publication Journal

of School Connections with the mission to publish high-quality articles

devoted to enhancing student learning and teaching practices from preschool

through high school. We are honored to have been appointed by Dr. Esposito

to serve as founding co-editors of this important journal.

In a knowledge-demanding era, the thirst for wisdom is ever burgeoning. As

a refereed journal,

JSC provides another outlet for intellectual contribution

and knowledge dissemination to reach national and international audiences

of both academics and practitioners. The achievement of this inaugural issue

is a result of a collaborative effort. We gratefully acknowledge our Editorial

Review Board and guest reviewers whose expertise has ensured that

JSC

publishes papers of the highest quality. We also thank our authors whose

scholarly contributions have introduced JSC.

As you will read, the four articles constituting this issue were derived from

quantitative as well as qualitative research using a variety of methodologies, such

as observations and questionnaires. The research findings presented clearly help

advance knowledge of topics bearing great significance to advancing teaching

and learning in the U.S. and elsewhere: from Lam and Lau’s quest to understand

factors contributing to Hong Kong teachers’ acceptance of peer coaching as a

professional development strategy; Freedson’s investigation of the role of literacy

instruction in the early literacy outcomes of young Spanish-speaking, English

language learners from low-income families; Viscovich, Eschenauer, Sinatra

and Beasley’s quasi-experimental study of the effects of various organizational

structures on children’s critical thinking; to Brown’s case study of teachers’ use

of comprehension strategies during core instruction.

As JSC aspires to continue making significant contributions to the education

field by publishing fine articles, we invite you to join our efforts by participating

as an expert reviewer of manuscripts or a contributing author. Your support

as a reader will also play an important role in realizing the mission of

JSC.

Together, we can help advance knowledge and translate research into practice,

thereby enhancing the learning of educators and students alike.

JENNIFER J.-L. CHEN DIANE H. TRACEY

1

Journal of School Connections

Fall 2008, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 3-24

SHUI-FONG LAM

University of Hong Kong

and

WING-SHUEN LAU

Education Bureau, the Government of Special Administrative

Region of Hong Kong

Teachers’ Acceptance of Peer Coaching:

Impact of Collegiality and Goal Orientation

Two studies were conducted to examine how collegiality and goal

orientation affected teachers’ acceptance of peer coaching as a means of

professional development. A total of 335 Hong Kong teachers participated

in these two studies (N = 70 for Study 1; N = 225 for Study 2). The

teachers completed a questionnaire that measured their acceptance of peer

coaching, perception of collegial school culture, and goal orientation. It

was found that collegiality and learning goal orientation were positively

associated with acceptance of peer coaching. Both studies showed that

when teachers perceived higher collegiality in their schools and preferred

learning to performance goals, they were more willing to participate in

peer coaching and evaluated it more favorably.

KEY WORDS: teacher development, peer coaching, collegiality,

goal orientation

To remain viable and productive in a society with constant changes,

organizations and individuals alike depend greatly on the ability to

learn. Schools and teachers are no exception. In 2001, the Hong Kong

government initiated a series of large-scale education reform measures

that cover all stages of education from early childhood to continuing adult

education (Education Commission, 2001). This reform is in line with the

large-scale education reforms that have been developing since the 1990s

in some western (Fullan, 2000) as well as Asian countries (Kim, 2004). It

is propelled by a strong demand from society emphasizing that students

should learn how to meet the challenges of an increasingly knowledge-

3

Lam & Lau

based and fast-changing world. New curricula in Hong Kong are required to

promote not only subject area knowledge but also general skills in students

(Curriculum Development Council, 2001). These skills include collaboration,

communication, and problem-solving skills. Under the mounting pressure

to provide quality education in this era of changes and reforms, schools can

no longer just rely on mechanisms for recruiting competent teachers to meet

new challenges. “Learning for life” is definitely an answer to the challenges

in this time of knowledge explosion and rapid changes. Teachers need to

learn, refresh, and polish their teaching skills continuously.

Among various forms of staff development activities, peer coaching

has been studied and recognized as an effective means to enhance teaching

quality (e.g., Bowman & McCormick, 2000; Gottesman & Jennings, 1994;

Hasbrouck, 1997; Hasbrouck & Christen, 1997; Joyce & Showers, 1983).

Peer coaching is a process of teachers helping teachers to reflect on present

practices, learn new skills, and solve classroom-related problems through

mutual goal setting, classroom observation and collegial feedback (Dalton

& Moir, 1991; Galbraith & Anstrom, 1995). This form of professional

development was first advocated by Showers (1984), who was concerned

about the transfer of professional learning experiences to classroom practices.

Traditional teacher development activities are usually in the form of one-shot

workshops or refresher courses that are conducted outside of the school day.

However, many educational researchers (e.g., Fullan & Stiegelbauer, 1991;

Gottesman & Jennings, 1994; Loucks-Horseley, Hewson, Love, & Stiles,

1998; Mousa, 2002) have been doubtful about the effects of these isolated

professional learning experiences that fail to provide on-site support for

and continual feedback on classroom practices. Brown, Collins and Duguid

(1989) argued that skills and strategies cannot transfer well if they are

not learned in situated contexts. In view of the inadequacies of traditional

professional learning activities, researchers and practitioners need to seek

alternative methods that support a teaching community’s development and

sustain continual professional growth for teachers (Glazer, & Hannafin,

2006). One such alternative is peer coaching.

Peer coaching is different from traditional activities which do not

provide on-site continual coaching. In contrast, it is based on continuous,

collegial interaction and support in the schools. Many researchers have

found that the use of peer coaching could maximize the transfer of

professional learning to actual practice in the classroom (Bowman &

McCormick, 2000; Hasbrouck, 1997; Hasbrouck & Christen, 1997; Joyce &

Showers, 1983; Kohler, Crilley, Shearer, & Good, 1997; Morgan, Menlove,

Salzberg & Hudson, 1994; Showers, 1984; Sparks, 1988). For example,

using a multiple baseline design, Morgan et al. (1997) found that peer

4

Teachers’ Acceptance of Peer Coaching

coaching increased the effectiveness of the pre-service teachers’ teaching

as indicated in students’ mastery of the learning task. Similarly, Kohler and

his colleagues (1997) found that peer coaching helped elementary school

teachers make more improvements in instructional approach and these

improvements were sustained in a follow-up or maintenance condition.

Despite the wide recognition of its effectiveness in teacher development,

peer coaching is often received by teachers with lukewarm support and even

outright resistance. Lam (2001) conducted a questionnaire survey with about

2,400 teachers in Hong Kong and found that over 25% of them indicated that

they did not welcome colleagues observing their classes. There is a subtle

resistance from teachers against having another adult in their classrooms.

Perhaps classroom isolation is one of the most pervasive characteristics

of teaching. Teachers in separate classes are usually isolated and detached

from one another’s work. An interesting remark made by Gottesman and

Jennings (1994) aptly described the isolation mentality of teachers: “Just

give me my students and let me close the door and teach my students” (p.

19). Isolation may protect teachers from inspection and intrusion, but it also

deprives them of the opportunities to reflect on crucial aspects of learning

that they could otherwise learn from and share with one another.

The resistance to peer coaching, ironically, contradicts the

recognition of its effectiveness in teacher development. This irony calls

for attention from educators and researchers who are concerned with

continuing teacher education. Since improving teaching quality is a

pressing concern, there is a need to identify the factors that may influence

the extent to which teachers support the practice of peer coaching so as to

capitalize on its benefits in teacher development. The present two studies

attempted to investigate such underlying factors.

School culture and collegiality

To understand the factors that affect teachers’ acceptance of peer

coaching, we cannot study teachers’ perception and behaviors in a

vacuum and ignore the wider social context of the schools. Hargreaves

(1988) argued that teaching quality is very much a product of the school

context and teacher personal factors. He further pointed out that teachers’

behavior is often affected by the environment around them. According

to Hargreaves, “teachers are actively interpreting, making sense of, and

adjusting to, the demands and requirements their conditions of work place

upon them (p.211).” This suggests that school environment, culture and

atmosphere may have a positive or negative impact on teachers’ behaviors

and responses which in turn affect their teaching performance.

In studying school conditions that foster organizational learning,

5

Lam & Lau

Leithwood, Jantzi and Steinbach (1998) found that a collaborative and

collegial school culture was a significant factor contributing to school

learning. Drawing on intensive case studies of mathematics and English

teachers in American high schools, Little (2003) also found that norms of

mutual support among teachers, informal sharing of ideas and materials,

respect for colleagues’ ideas and willingness to take risks in attempting

new practices were all important aspects associated positively with

teachers’ own learning. The interactions among teachers that focus on

actual classroom performance are potentially the most useful, and yet

also the most demanding because they subject teachers to peer scrutiny.

These interactions place teachers’ self-esteem and professional respect on

the line. If there is a lack of collegiality among teachers, peer coaching

can be a threatening experience. We therefore expect that collegiality is

an important organizational factor that determines teachers’ acceptance

of peer coaching as a means of professional development. When the

collegiality level is high in the school, teachers are more likely to practice

peer coaching. Conversely, when collegiality in the school is lacking,

teachers are reluctant to let other teachers into their classrooms. They will

neither open their teaching for observation and discussion, nor seek help

from other teachers when faced with difficulties and challenges.

Goal orientation

While collegiality is an important organizational factor that fosters the

practice of peer coaching, goal orientation may be an essential personal

factor that determines its acceptance among teachers. As peer coaching

exposes how teachers teach to the scrutiny of their peers, it can impose

tremendous psychological pressure on those who have high concerns

about getting a positive evaluation of their performance. They will spend

much time finding resources and preparing teaching materials in order to

perform better and look good in front of their peers. Lam’s survey (2001)

revealed that many Hong Kong teachers felt the psychological pressure to

perform well when their teaching was being observed by colleagues.

Teachers’ pressure to perform well in front of their peers may be a

consequence of their goal orientation. Dweck and her associates (Cain &

Dweck, 1995; Dweck, 1986; Dweck & Leggett, 1988) posited that people

may have different goal orientations in learning. Some people adopt

performance goals aimed at getting positive evaluations and avoiding

negative evaluations of their work, whereas others may adopt learning goals

targeted at achieving higher levels of competence instead of documenting

them. People who are more performance-oriented tend to avoid challenges

for fear of losing face when they are not sure of definite success (Dweck

6

Teachers’ Acceptance of Peer Coaching

& Legget, 1988, Grant & Dweck, 2003). They perceive negative feedback

as an indication of their low ability and thus will reduce effort and even

withdraw from the activity if they receive negative feedback. On the basis

of the above findings in goal orientation (Cain & Dweck, 1995; Dweck,

1986; Dweck & Leggett, 1988; Grant & Dweck, 2003), we expect that

when performance-oriented teachers are not sure of definite success,

they are more likely to reject peer coaching, which requires them to

be observed and open to others’ comments. In contrast, we expect that

learning-oriented teachers tend to welcome challenges even though they

are not sure of definite success. They tend to perceive feedback, either

positive or negative, as an input for growth and development. Compared

to performance-oriented teachers, they are more likely to persist and strive

under difficult conditions.

Depending on their goal orientation, teachers may perceive peer

coaching as either an opportunity to grow or a burden that requires them

to do much preparation and makes them subject to others’ appraisal or

evaluation. In the present studies, we expected that teachers who espoused

learning goals would accept peer coaching more readily than their

counterparts who espoused performance goals. In other words, acceptance

of peer coaching would be positively associated with learning goals but

negatively with performance goals.

Overview of the two studies

To investigate how collegiality as an organizational factor, and goal

orientation as a personal factor, are related to teachers’ acceptance of

peer coaching, we conducted two studies with teachers in Hong Kong,

a place where large-scale education reform has been launched in recent

years. On the one hand, the reform has highlighted the importance of

professional development and has urged Hong Kong teachers to learn,

refresh, and polish their teaching skills continuously. On the other hand,

the emphasis on accountability has pressured Hong Kong teachers to meet

performance standards and might have thereby encouraged the attainment

of performance goals. In view of these developments, it is meaningful to

examine how teachers in Hong Kong perceive and receive peer coaching

in a society where education reform is intensive.

The present research comprises two studies. The participants of Study

1 were the teachers of two schools that had previously participated in an

action research project on peer coaching (Lam, Yim, & Lam, 2002). These

teachers had tried peer coaching for a year and then were evaluated on this

particular form of professional development at the end of the project. Study

2 was a survey project with teachers who might not have practiced peer

7

Lam & Lau

coaching before. The participants of Study 2 were selected by a random

sampling procedure from various schools in Hong Kong. Although the two

studies targeted different teacher populations, we expected that teachers’

acceptance of peer coaching would be associated with collegiality and

goal orientations. It was assumed that the findings would be robust if both

studies indicated similar patterns of positive association among collegiality,

learning goals, and teachers’ acceptance of peer coaching.

Study 1

Method

In this study, we investigated how collegiality and goal orientations

associated with teachers’ acceptance of peer coaching in two schools that

had implemented peer coaching.

Sample and procedures

The project was initiated by a research team from the University of

Hong Kong and the Education Convergence. The Education Convergence

is an active educational body formed by a group of front-line educators

in Hong Kong. In response to a note of invitation in the newsletter of

the Education Convergence, four schools volunteered to participate in

the project. The research team visited all four schools that had indicated

interest. In each of these meetings, the principal and department heads of

the school were present. Different parties expressed their understanding and

expectations of peer coaching. Eventually only two schools were selected

because of their readiness for peer coaching and their compatibility of

beliefs and values with the other parties of the project. The principals and

department heads of these two schools had gained general support from

their teachers for the project. All the involved parties agreed to develop

peer coaching as a means of professional development detached from staff

appraisal. The principals were not involved in the classroom observation

and no records of the observation were filed in the appraisal or personnel

archives of the teachers.

The participating schools consisted of a primary school with 560

students and 38 teachers, and a secondary school with 900 students and 50

teachers. Both were government subsidized schools with students coming

primarily from low to middle socioeconomic backgrounds. Most of the

students resided in public housing estates.

This was a year-long project with an evaluation at the end of the

school year. The peer-coaching activities taking place in these two schools

were similar to the “lesson study” practiced by many Japanese teachers in

professional development (Fernandez, Cannon, Chokshi, 2003; Lewis &

8

Teachers’ Acceptance of Peer Coaching

Tsuchida, 1998; Shimahara, 1998). In a typical peer-coaching activity, four

or five teachers from the same department (e.g. science or language art)

discussed and reflected on their classroom teaching, designed and planned

teaching materials together, and, finally, were observed by and learned

from one another. These teachers first identified an instructional unit

(e.g. learning how to write expository articles) to study and then jointly

drafted a detailed lesson plan. One of them would teach the lessons to his

or her students, while the others observed. After the instructional unit was

completed, the teachers would meet to discuss their observations and ideas

for how to improve the lessons. This activity was used solely for staff

development purposes and was entirely independent from staff appraisal.

There were 28 peer-coaching activities in the primary school and 17 in the

secondary school during the year. Each peer-coaching activity, as indicated

earlier, comprised collaborative preparation for an instruction unit, in-

class observation of that instruction unit, and review discussion after that

instruction unit was over. The number of peer-coaching activities in each

school was decided by the teachers in consultation with their department

heads. All of the primary school teachers (N = 30) and about 80% of the

secondary school teachers (N = 40) participated at least once in the peer-

coaching activities.

After a year of experimenting with peer coaching as a means of

professional development, a questionnaire survey was conducted with the

teachers from both schools to evaluate the effectiveness of the project. In

the primary school, 30 teachers completed the questionnaires (response rate

= 75%); in the secondary school, 40 teachers completed them (response

rate = 80%). The participants were assured that no personal data would be

collected and that their identities would be kept anonymous. Hence, no

data about the participants’ age and gender were collected for the survey.

However, we did collect information about their teaching experience and

ranks. They had an average of 6.32 years of teaching experience (range =

1-25 years; SD = 6.43 years). About 29% of them held senior positions,

such as department heads, in their schools.

Measures

The questionnaire was written in Chinese and included items that

measured the teachers’ evaluation of the peer-coaching activity, their

willingness to participate, their perception of collegiality in their schools,

and their goal orientation. Except for the measure of goal orientation, the

teachers were requested to indicate, on a 6-point Likert-type scale, their

level of agreement or disagreement with a given statement in each of the

measures (from 1 = Strongly Disagree to 6 = Strongly Agree).

9

Lam & Lau

Perceived collegiality. This scale consisted of 10 items such as “there

are trustworthy colleagues I can turn to for advice if I have problems.”

These items measured friendship, collaboration, trust, and respect among

colleagues. They were adapted from the Social Provision Scale developed

by Baron and his colleagues (1990) and the Collegial Support Index

developed by Schonfeld (1990). The Cronbach’s alpha of this scale in this

sample was .81, indicating a good level of internal consistency.

Teachers’ goal orientation. The goal orientation of teachers was

measured by three hypothetical scenarios adapted from a staff development

program designed by Lam, Law, and Cheung (2000). In each scenario,

the teachers were asked to make a choice that would indicate their goal

orientation. For example, the teachers were asked what action they would

take if they were enrolled in a course on classroom management and the

instructor required them to video-tape one of the lessons they teach for

class discussion. Two choices were available: 1) “To video-tape a class

with a better learning attitude and classroom discipline so as to obtain

some episodes with good teaching performance;” and 2) “To video-tape

a class where the teacher did not have full confidence in managing the

discipline so as to seek the instructor’s and fellow classmates’ opinions for

improvement.” The former choice reflected an orientation of performance

goals, whereas the latter reflected an orientation of learning goals. The

former choice indicated a tendency to sacrifice learning for better

performance and positive evaluations. In contrast, the latter choice indicated

a desire to learn although one’s performance was on the line and negative

evaluations from others might be received. One point was assigned if the

teachers chose an action that reflected the espousal of learning goals, and

no point was assigned if they chose an action that reflected the espousal

of performance goals. The points of the three scenarios were aggregated

to indicate the extent to which the teachers endorsed learning goals versus

performance goals. The scores for this measure ranged from 0 to 3, with

a higher score indicating a higher endorsement of learning goals and a

lower endorsement of performance goals. The Cronbach’s alpha of the

three scenarios was .55 for this sample, indicating an acceptable but not

high level of internal consistency.

Teachers’ acceptance of peer coaching. This construct was measured

by two sets of questions. The first set pertained to the teachers’ evaluation

of the peer coaching activities with which they had experimented in their

schools, whereas the second set was about their willingness to participate

in the activities. To measure their evaluation, the teachers were requested

to indicate to what extent they agreed with the following two statements:

1) “The peer coaching activities have enhanced our teaching quality

10

Teachers’ Acceptance of Peer Coaching

effectively;” and 2) “The peer coaching activities have enhanced our

mutual communication and understanding.” To measure the teachers’

willingness to participate in the activities, they were asked to indicate

their agreement with the following three statements: 1) “Despite the time

constraint and difficulty in scheduling, I am willing to participate in peer

coaching;” 2) “Considering the time I have spent and the psychological

pressure I have encountered, I am still willing to support my school in the

development of peer coaching;” and 3) “Given the freedom to choose, I

shall not participate in similar activities.” The third statement was reverse

coded for the measurement of the construct of teachers’ acceptance of peer

coaching. A negative statement was included in the scale to minimize the

acquiescent response style problem (Ray, 1979). The average rating of

the five statements was used to indicate the teachers’ level of acceptance

of peer coaching. The Cronbach’s alpha of these five statements for this

sample was .85, indicating a high level of internal consistency.

Results

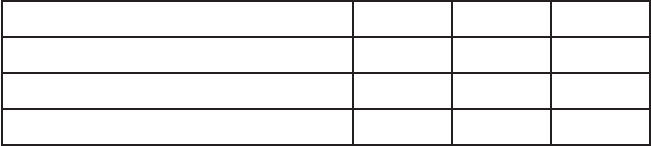

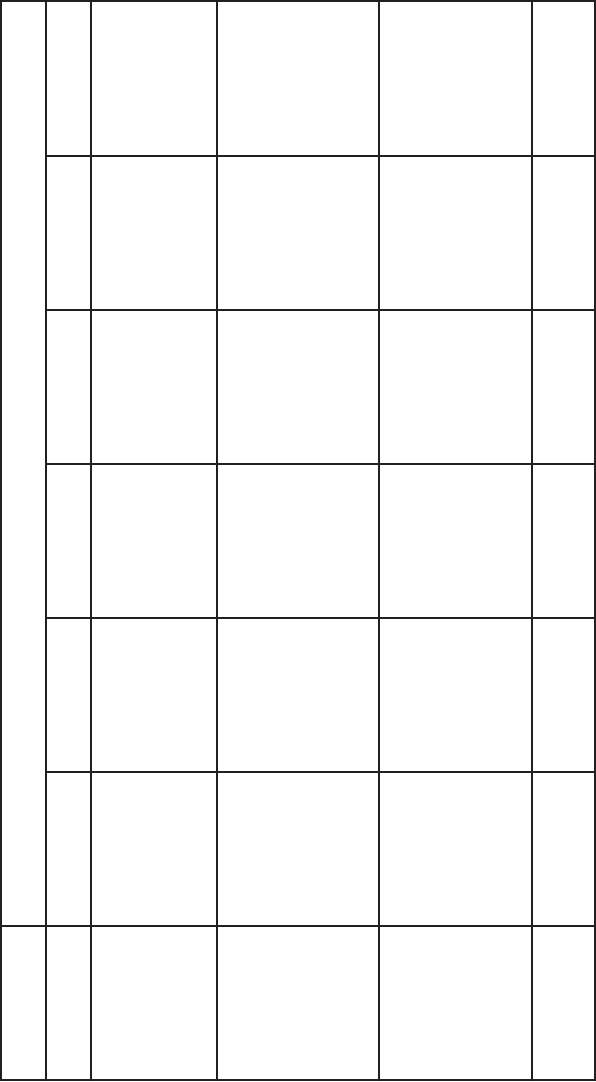

The correlation coefficients among the variables are presented in Table

1. All three variables were correlated positively. The more the teachers

perceived collegiality in their schools and the more the teachers endorsed

learning goals, the more they would accept peer coaching. The correlation

coefficients ranged from .35 to .47, indicating medium-sized effects.

11

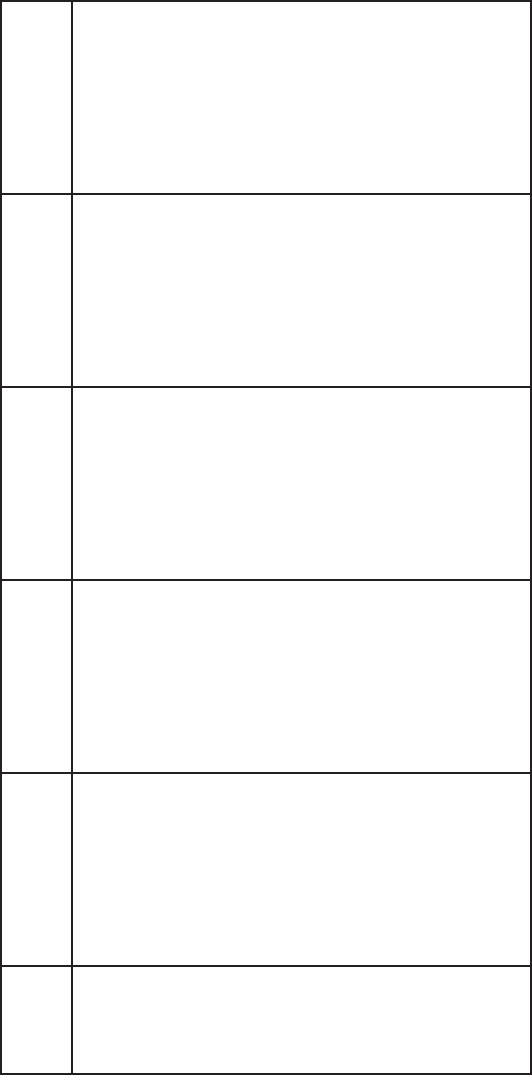

1 2 3

1. Perceived collegiality - .14* .19**

2. Teachers’ goal orientation .35** - .26**

3. Acceptance of peer coaching .47** .40** -

TABLE 1. Correlations of the Variables

**p < 0.01 * p < 0.05

Note. The correlation coefficients below the diagonal are results of Study 1

whereas the correlation coefficients above the diagonal are results of Study 2.

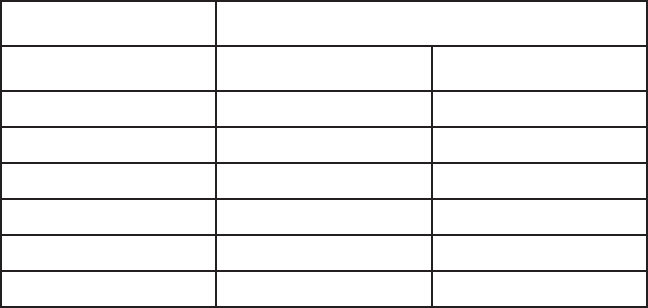

To test the predictability of perceived collegiality and teachers’ goal

orientation on teachers’ acceptance of peer coaching, we performed a

multiple regression analysis. The results are presented in Table 2. It was

found that teachers’ acceptance of peer coaching significantly predicted

their perception of collegiality in their schools (β = .38, p < .01) as well

as their goal orientation (β = .26, p < .05). That is, for every one unit

Lam & Lau

increase of acceptance of peer coaching, there would be .38 unit increase of

perceived collegiality and .26 unit increase in learning goals. Teachers who

perceived stronger collegiality in their schools and adopted learning goals

more than performance goals tended to have higher levels of acceptance of

peer coaching, as indicated by their better evaluations of the activities and

higher levels of willingness to participate in peer-coaching activities.

12

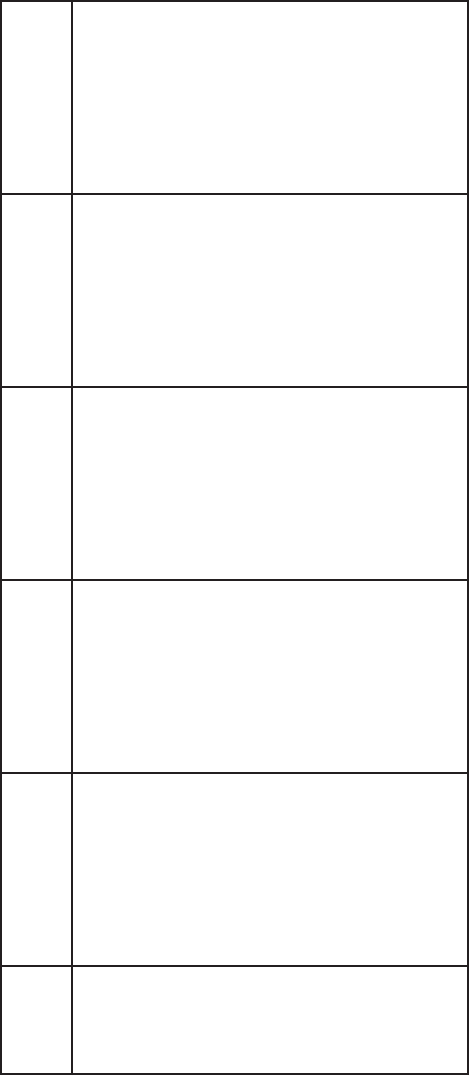

Independent Variables B SE B β

Study 1

Perceived collegiality .72 .21 38**

Teachers’ goal orientation

.30 .13 .26*

Study 2

Perceived collegiality .21 .08 .17**

Teachers’ goal orientation

.24 .06 .24**

TABLE 2. Summary of Multiple Regression Analyses for Perceived

Collegiality and Goal Orientation Predicting Acceptance of Peer Coaching

**p < 0.01 * p < 0.05

Note. R2 = .24 for Study 1; R2 = .10 for Study 2.

Discussion

The participants in Study 1 were teachers from the two schools who had

previously experimented with peer coaching. The variation of collegiality,

the organizational factor, was restricted because only two schools were

involved. Moreover, these two schools were different from typical schools

because they had a year-long trial on peer coaching, a

novice form of

professional development that is seldom practiced in Hong Kong. Lam

(2001) found that half of the Hong Kong respondents in her survey indicated

that they had never practiced classroom observation; that is, they had

never observed their colleagues’ teaching and neither had their colleagues

observed them in teaching. For the rest who responded that they had such

practice, their so-called observation was mostly an appraisal activity done

by supervisors about their teaching. Peer coaching is something new and

unfamiliar to most teachers in Hong Kong. To test if the findings of Study

1 could be generalized to other schools that had not experimented with

peer coaching, we conducted a survey with teachers selected by a random

sampling procedure. We would be able to confirm the positive associations

among collegiality, learning goal, and teachers’ acceptance of peer coaching

if the results of Study 2 could replicate those of Study 1.

Teachers’ Acceptance of Peer Coaching

Study 2

Method

In this study, we investigated how collegiality and goal orientations

associated with teachers’ acceptance of peer coaching in a randomly

selected sample of teachers who might not have had prior experience with

peer coaching.

Sample and procedures

The Hong Kong Professional Teachers’ Union is the largest professional

body of teachers in Hong Kong. A sample of 600 teachers was selected

randomly from its membership of 70,000. Questionnaires were mailed

to 300 primary school teachers and 300 secondary school teachers. The

respondents were requested to return the completed questionnaires in the

stamped envelopes provided by the researchers. Anonymity was guaranteed

for the survey. The participants were assured that no personal data would

be collected and their identities would not be known. The response rate

to the questionnaire was 42.5%, and 255 questionnaires were collected.

Among the 255 respondents, 43.3% were secondary school teachers and

56.7% were primary school teachers. Their average teaching experience

was 13.53 years (range = 1-35 years; SD = 9.31 years). About 38% of

them held senior positions, such as department heads, in their schools.

Measures

Except for the measures of teachers’ acceptance of peer coaching, all

measures used in Study 1 were applied again in Study 2. They included

teachers’ perceived collegiality and learning orientation. All the items in

the questionnaire were presented in Chinese.

Unlike the teachers in Study 1, the teachers in Study 2 might not have

experienced peer coaching previously. Many of them might not have

known what peer coaching exactly meant. To avoid any misunderstanding,

peer coaching was defined clearly in the questionnaire instructions. The

following definition was presented to the teachers: “In peer coaching,

teachers talk about and reflect on their classroom teaching, design and plan

teaching materials together, are observed by and learn from one another.

The activity is different from the usual practice of classroom observation

that is for staff appraisal. The focus is not on the performance of individual

teachers but on how teachers can pool their efforts to improve classroom

teaching. The observers and the observed can prepare a lesson together

before the observation and discuss their experience afterwards.”

The teachers were asked to evaluate the viability of peer coaching

in their schools and estimate how successful the activities would be if

13

Lam & Lau

practiced in their schools. Unlike in Study 1, we did not measure teachers’

evaluation of the peer coaching they had practiced in the previous year.

Instead, the teachers were asked to indicate their level of agreement and

disagreement with the following statements: 1) “I doubt if peer coaching

can improve teaching quality in my school;” and 2) “I believe that peer

coaching can enhance mutual communication and understanding among

colleagues in my school.” The first statement was reversed in coding.

To measure the teachers’ willingness, we asked them to indicate their

willingness to participate if their schools launched similar activities. They

were requested to indicate their levels of agreement and disagreement

with the following statements: 1) “If my school tries peer coaching, I

shall support it.” 2) “If my school tries peer coaching, I am willing to

let my colleagues observe my teaching.” 3) “Considering the time I may

spend and the psychological pressure I may encounter, I am still willing to

support my school in the development of peer coaching.” 4) “Given free

choice, I shall not participate in similar activities.” The fourth statement

was reversed in coding. Negative statements were also included in the

scale to minimize the acquiescent response style problem. It is always a

good practice to avoid one-way worded scales (Ray, 1979). The average

score of the above six items was used to indicate the teachers’ acceptance

of peer coaching. The Cronbach’s alpha of these six items in Study 2 was

.92, indicating high internal consistency.

Results

The correlation coefficients among the variables are presented in

Table 1 (see page 11). The coefficients.. The coefficients ranged from

.14 to .26. All of the variables were correlated positively, although the

magnitude was smaller than those in Study 1. To test the predictability

of collegiality and goal orientation, we regressed teachers’ acceptance of

peer coaching on these two variables. The results are presented in Table 2

(see page 12). It was found that teachers’ acceptance of peer coaching was

predicted significantly by their perception of collegiality in their schools

(β = .17, p < .01) as well as their goal orientation (β = .24, p < .01). For

every .17 unit increase of perceived collegiality and .24 unit increase of

learning goals, there would be one unit increase of acceptance of peer

coaching. Teachers who perceived stronger collegiality in their schools

and adopted learning goals more than performance goals tended to have

higher acceptance levels of peer coaching. They had higher expectations

of the activities and were more willing to participate in them. In summary,

14

Teachers’ Acceptance of Peer Coaching

the results of Study 2 replicated those of Study 1 even though the two

studies targeted different populations.

Discussion

Unlike the participants in Study 1, the teachers in Study 2 might

not have had prior experience with peer coaching. Their responses to

the questionnaire concerning peer coaching were based primarily on the

descriptions provided in the instructions. With reference to the hypothetical

scenario that peer coaching might be practiced in their schools, the

participating teachers estimated the effectiveness of this practice and

expressed their willingness to participate in it. The psychological process

involved in Study 2 was prospective instead of retrospective. In contrast,

the participants in Study 1 had practiced peer coaching for a year and

were asked to examine their experiences retrospectively. The participants

in Study 2 were asked to project their thoughts into the future, while the

participants in Study 1 were asked to review their practice in the past.

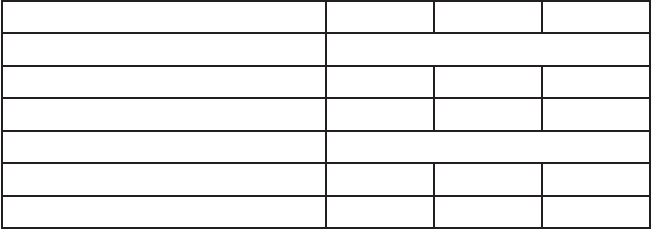

Despite the differences regarding the subjects’ exposure to peer coaching

as a novice staff development activity, the results of the two studies were

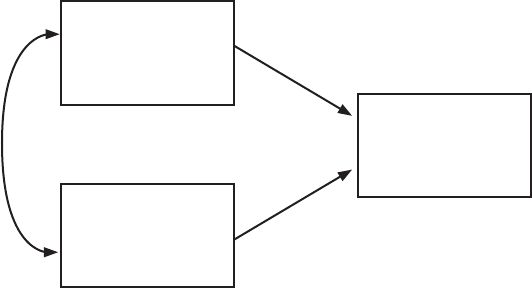

consistent (see Figure 1). They converged to show that teachers’ acceptance

of peer coaching was positively associated with their perception of

collegiality in their schools and their goal orientation.

15

FIGURE 1. The path diagram explaining the impact of perceived

collegiality and goal orientation on teachers’ acceptance of peer coaching.

Note. Coefficients not in parentheses are results of Study 1 whereas

coefficients in parentheses are results of Study 2.

Acceptance of

Peer Coaching

.25* (.24**)

.38** (.17**)

.35** (.14*)

Perceived

Collegiality

Learning Goal

Orientation

Lam & Lau

General Discussion

The results of the two studies were consistent with our hypothesis

that teachers would be more likely to accept peer coaching as a form of

professional development if they perceived strong collegiality in their

schools. This is consistent with the findings of previous studies that

collegial school culture was a significant factor contributing to school

learning (Leithwood et al., 1988; Little, 2003). The findings of the present

studies provide educators with insights about the conditions under which

to implement peer coaching in the schools to render it effective.

Peer coaching is a form of professional development based primarily

on continuous collegial interaction and support. If teachers do not see

collegiality in their schools, they are more likely to reject peer coaching.

As a result, when peer coaching is implemented in a school culture that

lacks collegiality, the chances of its success would be slim. Imposing peer

coaching administratively on teachers in a weak collaborative culture

will only result in contrived collegiality. In his micro-political critique

of collegiality, Hargreaves (1994) pointed out that contrived collegiality

is administratively regulated, compulsory, and implementation-oriented.

Under the conditions of contrived collegiality, teachers are required to

work together to implement the mandates from school administrators.

Instead of being empowered, teachers in contrived collegiality feel

that they are being coerced to conform. Therefore, the so called “peer

coaching” is not a genuine collaboration among teachers, but an empty

shell of administrative formality. In the worst case, it may induce an

administrative apparatus of surveillance and control under the aegis of

professional collaboration (Hargreaves & Dawes, 1990). However, in an

era of rapid educational reforms that value accountability and standards

(Sheldon & Biddle, 1998), there is a strong incentive for school leaders

to promote peer coaching without considering fostering a culture needed

for it to be successful. As stated by Little (1990), attempts at initiating

collaboration will not be successful if the school culture is incongruent

with collaboration. The results of the present studies are reminders of this

reality to educators. Peer coaching, or any other specific forms of induced

collaboration, will not be accepted wholeheartedly by teachers when they

do not perceive their school cultures as collaborative.

Some scholars (e.g., Little, 1990; Leithwood et al., 1988; Ponzio,

1987) have argued that an essential prerequisite for effective peer coaching

is the existence of a set of collegial relationships among teachers who

display qualities of trust, support and sharing. Does this argument imply

16

Teachers’ Acceptance of Peer Coaching

that educators should not initiate collaboration when school collaborative

culture is weak? We think that the answer depends on the deliberate attempt

s

on the part of the initiators. Grimmett and Crehan (1992) posited that any

attempt at initiating collegiality is inevitably contrived because it must

be engineered by some people, mostly administrators, in a place where

collegiality is not yet present. However, they also make a clear distinction

between an administratively imposed type and an organizationally induced

type of contrived collegiality. The former is undesirable, but the latter

could lead to a genuine collaborative culture.

Administratively imposed collegiality consists of “top-down” attempts

to manipulate teachers’ collaborative behaviors directly. Teachers are

mandated to collaborate. In contrast, organizationally induced collegiality

is characterized by “top-down” attempts at fostering “bottom-up” problem-

solving approaches to school improvement. This is achieved through

careful manipulation of the environment instead of teachers’ behaviors

such as compliance. Many strategies can manipulate the environment, for

example by adopting a small-scale trial before any large-scale change,

implementing peer coaching at a slow pace that corresponds with teachers’

acceptance, reducing teachers’ workload so that they have time to engage in

the activities, and ensuring that peer coaching differs from staff appraisal.

So far, the literature on contrived collegiality has mostly been

developed in the western cultures (Grimmett & Crehan, 1992; Hargreaves,

1994; Hargreaves & Dawes, 1990; Little, 1990; Leithwood et al., 1988;

Ponzio, 1987). Nevertheless, it has a certain degree of universality across

western and eastern cultures and seems to apply well in Hong Kong. Like

many western countries, Hong Kong has recently launched a large-scale

education reform. Teacher professional development is inevitably a top

concern and the teachers in Hong Kong are under pressure to engage in

peer coaching if their school administrators are eager to enforce changes.

Without knowing the factors that contribute to teachers’ acceptance of

peer coaching, one may develop contrived collegiality that is not genuine

collaboration among teachers but an empty shell of administrative formality.

Fortunately, the advice of Grimmett and Crehan (1992) about the distinction

between administratively imposed and organizationally induced types of

contrived collegiality also applies well to Hong Kong. With the careful

manipulation of the environment in which the school culture develops,

Lam and her colleagues (2002) successfully helped teachers in two Hong

Kong schools develop practices in peer coaching and turn organizational

induced contrived collegiality into genuine collegiality.

17

Lam & Lau

As shown in the results of the present studies, collegiality is essential

for teachers’ acceptance of peer coaching. However, it does not necessaril

y

mean that it is a prerequisite for the success of peer coaching. The

causality between the collegiality and peer coaching may not be linear.

Clarke and Hollingsworth (2002) argued that teacher changes are a cyclic

process with multiple entry points. They put forward an interconnected

model of professional growth in which circular causality is assumed. It is

possible that changes in school culture may lead to changes in practice of

professional development such as the adoption of peer coaching. Likewise,

it is also possible that changes in practices of professional development

may lead to changes in school culture. Collegiality in the schools may be

enhanced after teachers have experimented with peer coaching. In fact,

most teachers in Study 1 agreed with the statement that peer-coaching

activities had enhanced their mutual communication and understanding

with colleagues. Their average agreement with this statement was 4.99

on a 6-point Likert scale. It was possible that peer coaching had enhanced

their collegiality, which in turn would further facilitate their acceptance of

peer coaching.

In both studies, we found positive path coefficients between teachers’

goal orientation and their acceptance of peer coaching. The results showed

that when teachers endorsed learning goals more than performance

goals, they tended to be more accepting of peer coaching. These results

support Dweck’s (1986) claim that people who endorse learning goals

are more motivated to master new and difficult tasks despite the risk that

their competence may be judged negatively. To open one’s teaching for

observation and discussion can facilitate learning, but it can also incite

insecurity. The insecurity would be most intense for the teachers who

espouse performance goals because they are aimed at gaining positive

judgments and avoiding negative judgments from others. To avoid negative

judgment of their competence, they may choose not to participate in peer

coaching. In contrast, teachers who endorse learning goals are aimed at

increasing their competence. As a result, they would see peer coaching as

an opportunity for learning and thus would be more receptive to it.

Our findings about goal orientation bear similarity to those of

Fernandez et al. (2003), who attempted to develop lesson study among a

group of American teachers. They found that teachers might not benefit

from lesson study if a “researcher lens” was not applied to the examination

of lessons. When teachers play the role of researchers, their goal is to

investigate ways that can improve their lessons so that students can learn

18

Teachers’ Acceptance of Peer Coaching

better. However, Fernandez et al. (2003) reported that a number of teachers

in their study objected to selecting topics commonly taught at their grade

level. They argued that these topics were dry and boring. Instead, they

preferred selecting original topics that might be more entertaining and

perhaps more engaging for their colleagues who would observe the lesson.

Fernandez et al. (2003) commented that the preference of these teachers

indicated that they lost sight of the researcher lens. The presence of the

researcher lens is similar to learning goals in which making improvement

instead of impressing others are the focus. The current findings show that

when teachers are concerned with impressing their colleagues rather than

seeking ways collaboratively to improve their lessons, they are subscribing

to performance goals instead of learning goals.

The interpretation of the results about teachers’ goal orientation,

however, should be made with the caveat that teacher changes are a

cyclic process with multiple entry points. The relationship between goal

orientation and collegiality may be circular. Teachers’ goal orientation can

affect the collaborative culture in their schools but collaborative culture

can also affect teachers’ goal orientation reciprocally. How teachers

behave is often determined by the environment around them (Hargreaves,

1988). Pressure from keen competition and high-stake evaluations may

force teachers to adopt performance goals in lieu of learning goals. Lam,

Yim, Law, and Cheung (2004) found that Hong Kong students adopted

performance goals when they were under the pressure of normative

evaluation. The same psychological mechanism may also apply to

teachers. The results of the Lam’s survey (2001) revealed that over 60%

of classroom observations in Hong Kong were conducted in the format of

supervisors observing subordinates. When classroom observation involves

staff appraisal, teachers may endorse performance goals involuntarily. As

peer coaching is decoupled from staff appraisal, teachers are not pressured

to focus on performance goals. They may favor learning goals more after

experiencing this new form of non-threatening staff development. In the

present studies, teachers’ goal orientation was correlated positively with

perceived collegiality. This shows the intricate relationship between

personal factors and organizational factors.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are several limitations of the two studies. First, both are

correlational with cross-sectional data. According to Clarke’s and

Hollingsworth’s (2002) interconnected model of professional growth, we

19

Lam & Lau

speculated about circular correlations among personal and organizational

factors. However, the results of our studies did not provide evidence of

any causal relationship. Correlational data from cross-sectional studies

can only provide information about the degree of association among

the variables being investigated. To determine changes over time, future

studies may collect longitudinal instead of cross-sectional data. Study 1

had the potential to collect longitudinal data as it was a year-long project

that witnessed the development of peer coaching in two schools. Data

collected in the beginning of project can be compared with those collected

at the end of it. However, to perform lag-time analyses, the anonymity of

the teachers would be compromised because pre- and post- project data

must be matched by identity. To counteract any psychological pressure on

teachers that might jeopardize the development of peer coaching in the two

schools, the research team decided not to collect information about their

identity. In addition, the lack of complete demographic data, such as gender

and age, might limit the interpretation of the results. It is unknown if gender

and age would be correlated with the outcome variables under examination.

Furthermore, it is unclear whether the teachers’ prior experience with their

school principals impacted their acceptance of peer coaching.

Another limitation of the present studies lies in the measures of

variables. All of the data were self-reports from teachers. Self-report

data are not necessarily inferior, particularly when they pertain to the

attitudes, beliefs, and feelings of the participants. In the present studies, it

is legitimate to measure the teachers’ goal orientation and acceptance of

peer coaching by the self-report method. However, the measurement of the

collegiality would have been stronger if it were complemented by methods

other than teachers’ reports. Future studies may consider other methods

such as third-party observations and ratings.

Despite these limitations, the present studies have contributed to the

existing body of knowledge on peer coaching. Both studies produced

similar results, showing that collegiality and learning goals were

associated positively with acceptance of peer coaching among teachers in

Hong Kong. It was found that teachers who perceived strong collegiality

in their schools and adopted learning goals were more inclined to accept

peer coaching, a professional development activity that is based mostly on

continuous collegial interaction and support in the schools. Findings from

our studies are helpful to educators who are interested in developing peer

coaching for more effective teaching in this time of education reform.

20

Teachers’ Acceptance of Peer Coaching

References

Baron, R. S., Cutrona, C. E., Russell, D. W., Hicklin, D., & Lubaroff, D. M.

(1990). Social support and immune function among spouses of cancer

patients. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 344-352.

Bowman, C. L., & McCormick, S. (2000). Comparison of peer coaching

versus traditional supervision effects. The Journal of Education

Research, 93,

256-261.

Browne, D., S., Collins, A., Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the

culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18, 32-42.

Cain, K. M., & Dweck, C. S. (1995). The relation between motivational

patterns and achievement cognitions through the elementary school

years. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 41, 25-52.

Clarke, D., & Hollingsworth, H. (2002). Elaborating a model of teacher

professional growth. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18, 947-967.

Curriculum Development Council (2001). Learning to learn: Life-long learning

and whole-person development. Hong Kong: Government Printer.

Dalton, S., & Moir, E. (1991, September). Evaluating LEP teacher training

and in-service programs. Paper presented at the Second National

Research Symposium

on Limited English Proficient Student Issues.

Washington, DC.

Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American

Psychologists, 41, 1040-1048.

Dweck, C. S., & Legget, E. L. (1988).

A social-cognitive approach to

motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95,

256-273.

Education Commission (2001). Reform of the education system in Hong

Kong. Hong Kong: Government Printer.

Fernandez, C., Canon, J., & Chokshi, S. (2003).

A US-Japan lesson study

collaboration reveals critical lenses for examining practice. Teaching

and Teacher Education, 19,

171-185.

Fullan, M. (2000). The return of large-scale reform. Journal of Educational

Change, 1, 5-28.

Fullan, M. G., & Stiegelbauer, S. (1991).

The new meaning of educational

change (2nd ed). New York: Teachers College Press.

Galbraith, P., & Anstrom, K. (1995). Peer coaching: An effective staff

development model for educators of linguistically and culturally

diverse students. Directions in Language and Education, 1, 2-8.

Glazer, E. M., & Hannafin, M. J. (2006).

The collaborative apprenticeship

model: Situated professional development within school settings.

Teaching and Teacher Education, 22,

179-193.

Gottesman, G.L., & Jennings, J.O. (1994). Peer coaching for educators

.

Lancaster: Technomic.

21

Lam & Lau

Grant, H., & Dweck, C. S. (2003). Clarifying achievement goals and their

impact. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 541-553.

Grimmett, P. P., & Crehan, E. P. (1992). The nature of collegiality in

teacher development: The case of clinical supervision. In M. Fullan, &

A. Hargreaves (Eds.), Teacher development and educational change

(pp. 56-85). London: Falmer Press.

Hargreaves, A. (1988). Teaching quality: A sociological analysis. Journal

of Curriculum Studies, 20, 211-231.

Hargreaves, A. (1994).

Changing teachers, changing times: Teachers’

work and culture in the postmodern age. London: Cassell.

Hargreaves, A., & Dawe, R. (1990). Paths of professional development:

Contrived collegiality, collaborative culture, and the case of peer

coaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 6, 227-241.

Hasbrouck, J. E. (1997). Mediated peer coaching for training pre-service

teachers. The Journal of Special Education, 31, 251-277.

Hasbrouck, J. E., & Christen, M. H. (1997). Providing peer coaching in

inclusive classrooms: A tool for consulting teachers. Intervention in

School and Clinic, 32, 172-177.

Joyce, B. & Showers, B. (1982). The coaching of teaching.

Educational

Leadership, 40, 4-10.

Kim, J. W. (2001). Education reform policies and classroom teaching in

South Korea. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 14(2),

125-145.

Kohler, F. W., Crilley, K. M., Shearer, D. D. & Good, G. (1997).

Effects

of peer coaching on teacher and student outcomes. The Journal of

Educational Research, 90, 240-250.

Lam, S.-f. (2001). Educators’ opinions on classroom observation as a

practice of staff development and appraisal. Teaching and Teacher

Education, 17, 161-173.

Lam, S.-f., Yim, P.-s., & Lam, T. (2002). Transforming school culture: Can

true collaboration be initiated? Educational Research, 44, 181-195.

Lam, S.-f., Yim, P-s., Law, J., Cheung, R. (2004). The Effects of competition

on achievement motivation in Chinese classrooms. British Journal of

Educational Psychology, 74, 281-296.

Lam, S.-f., Law, J., & Cheung, R. (2000). Enhancement of learning

motivation in the schools: program for teacher development. Hong

Kong: Education Department.

Leithwood, K., Jantzi, D., & Steinbach, R. (1998). Leadership and other

conditions which foster organisational learning in schools. In K.

Leithwood & K. S. Louis (Eds.), Organisational learning in schools

(pp. 67-93). Swets & Zeitlinger Publishers.

22

Teachers’ Acceptance of Peer Coaching

23

Lewis, C., & Tsuchida, I. (1998). A lesson is like a swiftly flowing

river: How research lessons improve Japanese education.

American

Educator,

22, 12-17 & 50-52.

Little, J. W. (1985). Teachers as teacher advisors: the delicacy of collegial

leadership. Educational Leadership, 43, 34-36.

Little, J. W. (1990). The persistence of privacy: autonomy and initiative in

teachers’ professional relations. Teachers College Record, 91,

509-536.

Little, J. W. (2003). Inside teacher community: Representations of

classroom practice. Teachers College Record, 105, 913-945.

Loucks-Horseley, S., Hewson, P. W., Love, N., & Stiles, K. E. (1998).

Designing professional development for teachers of science and

mathematics. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Morgan, R. L., Menlove, R., Salzberg, D. D, & Hudson, G. (1994). Effects

of peer coaching on the acquisition of direct instruction skills by low

performing preservice teachers.

The Journal of Special Education,

28, 59-76.

Mousa, C. (2002). Learning to teach with new technology: Implications

for professional development. Journal of Research on Technology in

Education, 35, 272-289.

Ponzio, R. C., (1987). The effects of having a partner when teacher study

their own teaching. Teacher Education Quarterly, 14, 25-40.

Ray, J. J. (1979). Is the acquiescent response style problem not so mythical

after all? Some results from a successful balanced F scale. Journal of

Personality Assessment, 43, 638-643.

Schonfeld, I. S. (1990). Psychological distress in a sample of teachers.

Journal of Psychology, 124,

321-338.

Sheldon, K. M., & Biddle, B. (1998). Standards, accountability, and school

reform: Perils and pitfalls. Teacher College Record, 100, 164-180.

Shimahara, N. K. (1998). The Japanese model of professional development:

Teaching as craft. Teaching and Teacher Education, 14,

451-462.

Showers, B. (1984). Peer coaching: A strategy for facilitating transfer

of training. Report to the U.S. Department of Education. Eugene,

Oregon: Center for Educational Policy and Management, University

of Oregon. ERIC EC 271 849.

Singh, K. & Shifflette, L.M. (1996). Teachers’ perspectives on professional

development. Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 10,

145-160.

Sparks, G. M. (1988). The effectiveness of alternative training activities in

changing teaching practices. American Educational Research Journal,

23, 217-225.

Lam & Lau

ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

Shui-fong Lam is an Associate Professor in the Department of Psychology

at the University of Hong Kong. She obtained her bachelor’s degree and post

graduate diploma in education from the Chinese University of Hong Kong,

master’s degree (counseling psychology) from the University of Texas, and

doctoral degree (school psychology) from the University of Minnesota.

Since 1994, Dr. Lam has been teaching in the Department of Psychology

at the University of Hong Kong. Her research interests lie in achievement

motivation, parenting, and instructional strategies. She is also concerned

with the improvement of psychological services in school system.

Wing-shuen Lau is an educational psychologist in the Education Bureau,

the Government of Special Administrative Region of Hong Kong.

She obtained her bachelor’s degree and master’s degree (educational

psychology) from the University of Hong Kong, post graduate diplomas

in psychology and education from the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Since 2000, Ms. Lau has been working as an educational psychologist

and providing school-based psychology services to students with diverse

needs. She is not only involved in direct services and case work with a

remedial nature but also indirect services and system work with the

purpose to enhance the learning environment for students.

Correspondence should be addressed to Shui-fong Lam, Department of

Psychology, University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong, China. E-

mail: [email protected].

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

This research project was funded by the Quality Education Fund of the

Hong Kong Government and the Committee on Research and Conference

Grants at the University of Hong Kong. We are grateful to Mr. C. T. Chan,

Ms. Y. S. Cheung, Mr. S. Y. Chiu, Mr. K. K. Choi, Ms. Y. Y. Fung, Ms.

P. W. Leung, Dr. A. Ma, Mr. P. W. Tam, Dr. E. Tsang, Mr. M. O. Wong,

and Mr. C. H. Wu for their advice and assistance in Study 1. We are also

grateful to the Education Convergence and the Hong Kong Professional

Teachers’ Union for their assistance in Studies 1 and 2 respectively.

24

25

Journal of School Connections

Fall 2008, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 25-62

MARGARET J. FREEDSON

Montclair State University

Supports for Dual Language

Vocabulary Development in

Bilingual and English Immersion

Pre-kindergarten Classrooms

The links between high-quality preschool language and literacy

experiences and vocabulary growth are increasingly well-documented for

monolingual English-speakers from low-income backgrounds. This article

explores language and literacy instruction and bilingual vocabulary gains

in preschool classrooms serving low-income Spanish-speaking English

language learners (ELLs). Group language and literacy instruction was

observed in six full-day pre-kindergarten classrooms representing three

broad instructional models: predominantly Spanish-language bilingual

instruction, mixed Spanish-English bilingual instruction, and English

immersion instruction. The fall and spring receptive vocabulary of 53

Spanish-speaking 4- to 5-year-olds was measured in Spanish and English

to determine the classrooms in which children made the greatest vocabulary

gains in each language. Children made the greatest Spanish vocabulary

improvements in bilingual classrooms with strong supports for Spanish

language development that included reflective read-aloud conversations

and explicit teaching of Spanish vocabulary. English vocabulary gains

were greatest when teachers scaffolded student participation in English

language instruction and provided Spanish language support. Implications

for practice and future research are discussed.

KEY WORDS:

bilingual, preschool, low-income, Spanish-speaking

English language learners

The last decade has seen the rapid expansion of publicly-funded

preschool services accompanied by growing diversity in the U.S. preschool

Freedson

population. In July of 2007, an estimated 4.9 million children under age

five – nearly one in four – were of Hispanic origin (U.S. Census Bureau,

2007). Among Hispanic children in this age group, a large proportion

comes from homes where Spanish is the primary language spoken and

thus begin school as English language learners (ELLs). Extrapolating from

the available data, ELLs of Hispanic backgrounds represent an estimated

23% of Head Start and 18% of current state pre-kindergarten enrollments

nationwide, and these numbers are projected to increase well into the future

(Collins & Ribeiro, 2004; Hamm & Ewen, 2005). Disproportionately and

persistently high rates of academic underachievement complicate long-

term prospects for this population of young learners (Garcia, Jensen &

Cuellar, 2006). Hispanic children tend to begin school with fewer literacy-

related experiences and skills (Goldenberg, 2001; Lee & Burkam, 2002;

Vernon-Feagans, 2001) and to score well below their non-Hispanic White

and Asian-American peers in reading throughout the school years, ending

up on average about four years behind (August & Hakuta, 1997; August &

Shanahan, 2008; Schnieder, Martinez & Owens, 2006).

Participation in high-quality preschool offers one of the most

potentially beneficial redresses to help close the gap in reading achievement.

Preschool programs that provide rich language and literacy environments

have been shown to enhance acquisition of many early literacy skills that

reliably predict later reading achievement – oral language, phonological

awareness, and print knowledge – with stronger effects observed for

more economically disadvantaged and Hispanic children (Dickinson &

Sprague, 2001; Gormley, Gayer, Phillips, & Dawson, 2005; NELP, 2007;

IRA-NAEYC, 1998; Snow, Burns & Griffin, 1998).

This research examined preschool practices that support Spanish-

speaking ELLs development in one key early literacy domain – vocabulary.

The links between vocabulary size and literacy development are increasingly

well documented in the literature on reading and language development

in monolingual English-speakers (NELP, 2007; Snow, Burns & Griffin,

1998). Children with larger vocabularies typically have more developed

phonological sensitivity as preschoolers (Burgess & Lonigan, 1998) and

better reading comprehension as they progress through the elementary

grades (Hart & Risley, 1995; Snow, Roach, Tabors & Dickinson, 2001).

A recent review of more than 300 empirical studies by the National Early

Literacy Panel produced average correlations between receptive vocabulary

in children five and under and later decoding and comprehension skills of

.35 and .32 respectively (NELP, 2007). Large social class differences in

children’s vocabulary knowledge have been documented starting at age three

and represent a challenge for preschool educators (Hart & Risley, 1995).

26

Dual Language Vocabulary Development

Though far less is known about early literacy in bilingual children, there

is accumulating evidence that oral language skills broadly construed, and

vocabulary specifically, are also foundational to literacy development in

young Spanish-speaking bilinguals (Manis, Lindsey & Bailey, 2004; Rinaldi

& Paez, 2008). Reese, Garnier, Gallimore and Goldenberg (2000) found

that children with greater emergent Spanish literacy skills, including oral

story comprehension, and greater oral proficiency in English at kindergarten

entry, attained higher levels of English reading achievement in middle school,

suggesting that early proficiencies in both languages impact long-term literacy

outcomes. This conclusion is supported by the work of Rinaldi and Paez

(2008) who found that both English and Spanish vocabulary in preschool

predicted English word reading ability in first grade. Not surprisingly,

limitations in depth and breadth of vocabulary are implicated in many of the

difficulties older ELLs experience with English text comprehension (August,

Carlo, Dressler & Snow, 2005). Educational practices that can help close

the substantial vocabulary gaps between low-income, Spanish-speaking

bilinguals and their monolingual peers are therefore worthy of attention

(Snow & Kim, 2001; Tabors, Paez & Lopez, 2003).

One of the primary impetuses for the current preschool expansion is

the potential impact of high-quality preschool experiences on language

and literacy learning. Specific preschool practices linked to better language

outcomes among ethnically diverse, low-income English speakers include

reading books aloud (Arnold & Whitehurst, 1994; Dickinson, 2001; NELP,

2007), vocabulary-rich teacher-child interactions (Dickinson & Smith,

1994), and opportunities for meaning-focused free play (e.g. dramatic

play, playing with blocks, etc.) (Connor, Morrison & Slominski, 2006).

The best-researched of these practices is reading aloud, which has been

shown to have a consistently positive impact on vocabulary acquisition,

particularly when children’s active participation is encouraged using

practices such as dialogic reading (Arnold & Whitehurst, 1994; NELP,

2007) and analytic book conversations (Dickinson, 2001).

Unfortunately, the literature offers far less guidance on effective

preschool literacy practices for ELLs. Existing research on ELL preschool

instruction tends to fall into three categories: 1) experimental or quasi-

experimental evaluation studies focused on language of instruction,

2) qualitative studies of classroom communication, and 3) intervention

studies of specific practices to enhance early literacy acquisition. From the

language of instruction research, there is emerging evidence that bilingual

instruction can enhance children’s language and literacy outcomes in

both the home language and English (e.g. Barnett et al, 2007; Campos,

1995; Gormley, 2007). For example, Barnett et al. (2007) reported on

27

Freedson

an experimental comparison of a two-way bilingual immersion preschool

program in which native Spanish-speaking children alternated weekly

between English and Spanish classroom environments, and a monolingual

English immersion program that used English as the primary medium of

instruction. Barnett et al. found no significant differences between the

two groups of children on measures of English receptive vocabulary or

other English literacy skills, while children in the bilingual program made

significantly greater gains on Spanish language measures. In these and

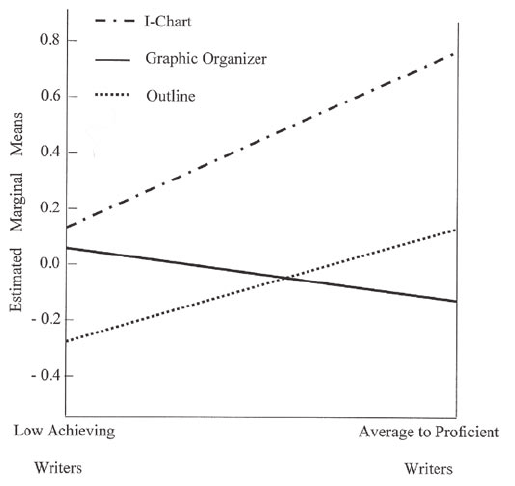

other such studies (e.g. Campos, 1995; Gormley, 2007; Paul & Jarvis,